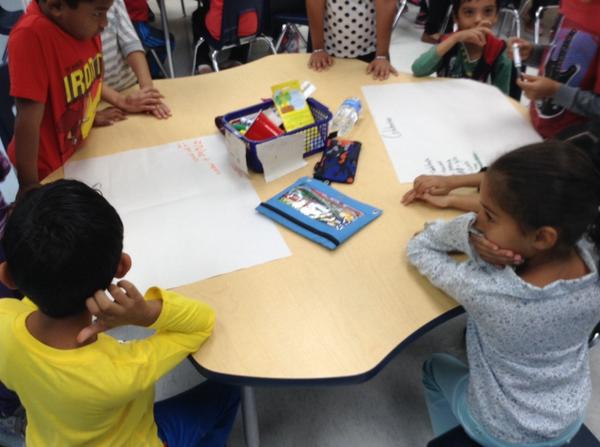

My classroom hard at work

For me a this can summed up in five words: Adaptable, Patient, Critical Thinkers, and Creators.

Adaptable:

The world is changing very rapidly and learners need to be able to change with it. Our students and us need to be able to move at that rapid base and use information as it comes.

Patient:

As the world changes answers may not always be there but they can be. With the right amount of patients any answer is possible

Critical Thinker:

This changing world does not need more complacent workers but thinkers. People that will change the world for the better. Learners also need to be able to sift through the endless streams of information to use it in a proper use.

Creator:

Learners in the 21st century also need to be creators of information and creators of ideas. Learners using the above skills will be able to generate ideas, products and information in order for others to learn.

My further questions:

1) How do we teach to these skills?

2) How do we prepare ourselves and students to use these skills?

3) Am I missing anything?

I apologize as I am a little over in my word count but hopefully its short enough.

This blog post is part of #peel21st Amazing blog hop. Check out these other amazing Peel Bloggers on this subject:

- Jim Cash – http://makelearn.org/

- Susan Campo – http://susancampo.ca

- Shivonne Lewis-Young – http://slewisyoung.wordpress.com

- Greg, Pearson – http://leaderinadigitalworld.blogspot.ca

- Phil Young – http://sphillipyoung.wordpress.com

- James Nunes – http://joyousteaching.blogspot.ca

- Donald, Campbell – http://ateachingyear.wordpress.com

- Ken Dewar – https://mysite.peelschools.org/personal/P0031112/Blog/default.aspx

- Graham Whisen – http://ideaconnect.edublogs.org/

- Heather Lye – http://teachinginspirations.blogspot.ca/

- Lynn Filliter – http://assessmentgeek.edublogs.org

- Debbie Axiak – http://debbieaxiak.blogspot.ca

- Alicia Quennell – http://aliciaquennell.blogspot.ca/

- Jonathan So – http://www.Mrsoclassroom.blogspot.ca

- Jim Blackwood – http://jimmyblackwood.wordpress.com

- Jason Richea – http://beyondangrybirds.blogspot.ca/

- Tina Zita – http://misszita.wordpress.com

- Sean Broda – http://mrseanbroda.blogspot.ca/

- Josh Crozier – http://joshcrozieredu.wordpress.com/

- Engy Boutros – http://engyboutros.wordpress.com/